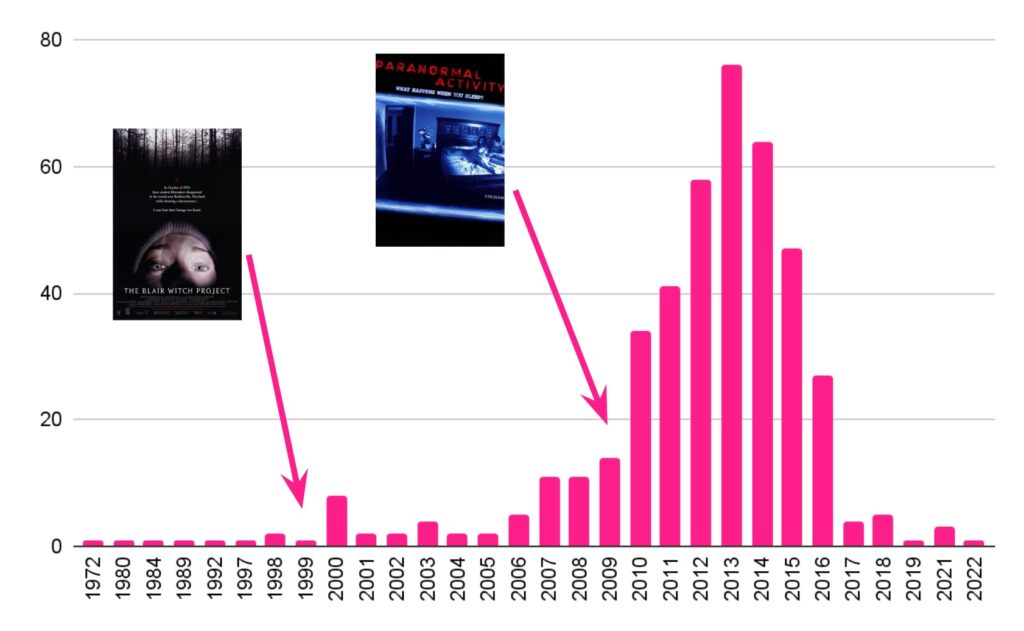

I recently resurrected an old presentation I gave at Twitch and shared a new version with students in Justin Winter‘s AI Producing class at LMU. This post is a recap!

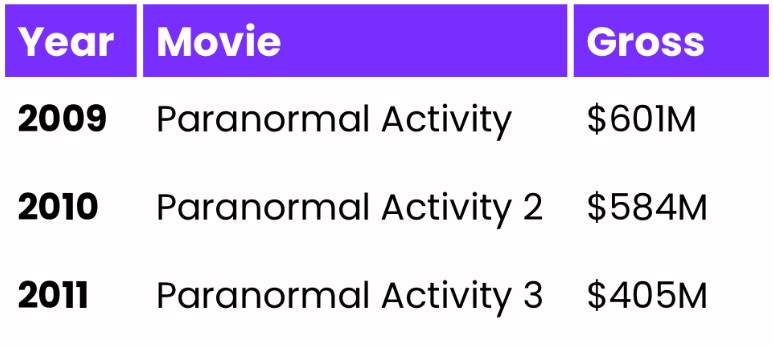

15 years ago, Paranormal Activity was released, just in time for Halloween in 2009. It was a viral phenomenon and the highest grossing horror movie of the year. The momentum was so powerful that Paranormal 2 and 3 became the highest grossing horror films in 2010 and 2011.

This was an industry-shifting movie for many reasons (the beginning of Blumhouse’s low-budget model and the marketing campaign1 among them), but I want to focus on one unexpected upshot you won’t see unless you dig into the data like I have: Paranormal Activity met very unique conditions in the market which caused a new genre to emerge. It’s a case study in how niche content can go mainstream…and how sometimes, it doesn’t.

PA was originally made for just $15,000 as a “found footage” horror movie. The premise is that we’re viewing “real” home video footage of an event that has been edited together after the fact. This masterful style gives the film creative license to have all the warts and imperfections which come with something user-generated. The low budget made it outrageously profitable. PA appeared in film festivals in 2007. It was scooped up by Paramount for only $350,000, who invested another $200,000 and widely released it in 2009, earning $601M (a phenomenal 1000x ROI for Paramount).

Highest Grossing Horror Films by Year: 2009-2011

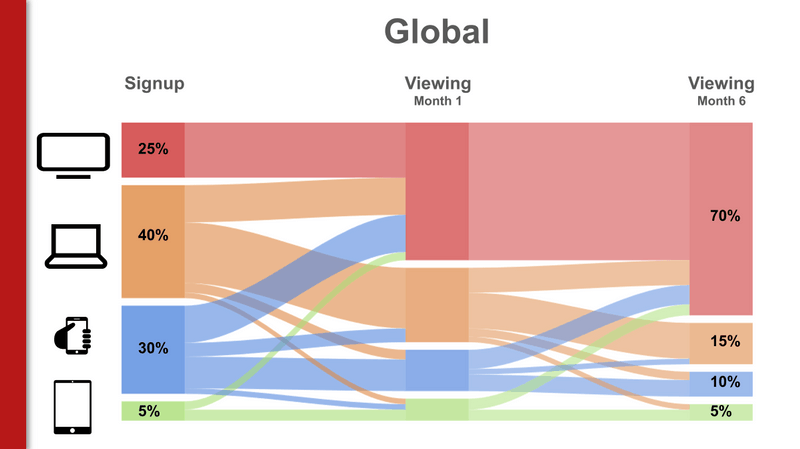

That’s all great for the individual franchise. But it’s even better for the film community because it kickstarted a new genre. Right after after PA comes out (2007 in festivals, 2009 wide release), independent filmmakers and major studios began creating hundreds of new found-footage horror movies. Have a look at this data I pulled from IMDb, charting the number of found footage horror movies since the 70s:

Number of Found Footage Horror Movies Released per Year

As you can see, >80% of all found footage horror was made after PA. Why? Because PA helped people clearly see the template for this content: do away with high-cost talent, lighting, music, production value – don’t even invest in visual effects and gore. It conveyed a formula for the genre which others copied.

You’re probably already getting ahead of me though… why am I giving all this credit to Paranormal Activity? There’s one more bump on this graph.

Indeed, 10 years prior, The Blair Witch Project debuted. But only a handful of found footage movies come out after this disruptive original indie. So Paranormal Activity inspired countless imitators and a whole new genre while Blair Witch does not. Why?

Oddly, popularity has nothing to do with it. Nor do economics. It’s smart to expect those drivers: popularity drives the zeitgeist which drives filmmaker inspiration. And economics compel producers and studios to invest in new genres. But in reality, Blair Witch was more popular and economically successful than PA. Nominally, Blair Witch made $604M in the box office, which is a little more than PA. And if we adjust for inflation, Blair Witch made $1.3B by today’s standards. So it’s unlikely that economics or viewership made the difference.

At two different times, very similar movies are released, both to very large audiences, both extremely profitable. But the second one has a knock-on effect of inspiring copies and the other does not. When I give this lecture IRL, we stop here and mine for different theories from the class (and I’d be curious to hear yours too!). There is no right answer. However, my hypothesis is that one macro theme captures many of the drivers: technology lowered the barrier of entry for this type of filmmaking.

In the 10 years between 1999 and 2009 there were multiple technological developments in entertainment which make copy cats of PA far more viable. DV cameras spread with the Panasonic DVX100 and Canon XL2 introducing a “prosumer” category (and eventually DSLRs like the Canon 5D). Non-linear and prosumer editing software like Final Cut Pro gains rapid market share and becomes available to consumers at a lower price point (accelerated with piracy as distribution) plus iMovie is bundled with Macs in 1999. HD video becomes widely adopted which doubles the resolution of a home movie. Online distribution and promotion become possible through YouTube and crowdfunding platforms. I’d even argue that software and websites for staffing/coordination hit more of a stride around 2009 (craigslist, Celtx, MySpace). Even the more qualitative cultural changes (like normalization of UGC and shaky cameras) are dependent on these technologies’ proliferation.

Imagine trying to make Blair Witch before all of this. Editing a movie required a special combination of Avid software and hardware rented from a post house on a per-hour basis (the creator of Blair Witch had access to these computers through his day job). The Blair Witch filmmakers found their cast through an ad in a physically printed magazine. Even in its simple, “home movie” form, Blair Witch was intimidating to replicate.

Paranormal Activity’s impact isn’t just a story of creative inspiration; it’s an example of how technological accessibility plays a parallel role in trendsetting. In the years between The Blair Witch Project and Paranormal Activity, it took dozens of technologies across the filmmaking supply chain to unlock a new genre. As we consider AI’s potential in entertainment, I like to consider possibilities like this one. AI is poised to do for fringe content what DV cameras and non-linear editing did for found-footage. Yes we’ll lose some jobs but in those particular areas (VFX, stock footage), barriers to entry will come down and enable new talent. I predict we’ll see many more new genres proliferate, inspired by innovative boundary-pushers with the right timing. Just as we saw with found footage, by reducing production costs and creative limitations, AI will enable niche formats tailored to diverse audiences.

Thanks to Scott Brooks and Ryan Latchmansingh for reading drafts of this!

- The guerrilla marketing campaign for Paranormal Activity could be its own case study. In trailers and on social media, ads asked fans to “demand” online that the movie come to their local theater. Then, as the movie spread to more screens, the ads showed off the number of new screens and proclaimed “you demanded it!” Trailers even utilized night vision footage of folks’ shocked reactions in theaters. Most likely, distributors had to commit to rolling out the movie nationwide months in advance because of the complexity of P&A– so the social proof of “you demanded it” was as much a hoax as the footage in the movie. ↩︎