I’ve been thinking a lot about the rumor of Apple’s hardware and content subscription bundle. The idea — whether it actually happens or not — is that they’d create a very expensive subscription of $80/month or so that bundles Apple Music, the new Apple original content, Apple Care, iCloud and a new iPhone every year. This is very much a rumor but very viable avenue posited here and by Matthew Ball at Redef.

This immediately reminds me that for years, Americans paid $100+ per month for another expensive hardware and content bundle: cable TV. I remember the salesman coming to my home and explaining to my parents what cable TV included. It was much more than TV, because before the internet, that box was your only gateway to many things. It was movies, music channels, educational programming for your kids, breaking news, live concerts and the hardware to make it all look beautiful on your only screen.

One way to frame Apple’s rumored hardware/content bundle is that they attract you with their device ecosystem (hardware) and then keep you hooked with their shows and music (content). The phone and its TV and cloud components are already a huge draw for audiences so their content can play the role of keeping users engaged there by making that ecosystem useful on a daily basis.

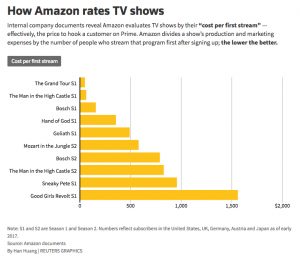

This got me thinking… maybe content isn’t really an effective audience awareness or acquisition tool AT ALL. Maybe, when all the cards fall, content is just the retention piece of a recurring payment business model and other elements of the bundle are what bring you in the door. This is somewhat reflected by the calculus Amazon did around their original video: it turned out that prestige TV shows like Mozart in the Jungle and Man in the High Castle weren’t such an efficient acquisition tool for Prime.

Check out how this thinking might apply to other businesses. I’ll use this analogy: come for X (acquisition); stay for content (retention).

- Apple hardware/content bundle – Come for the hardware ecosystem; stay for Oprah.

- Amazon Prime – Come for free shipping; stay for Nicole Kidman.

- HQ — Come for a cash prize; stay for the trivia.

- Facebook — Come for your friends; stay for Facebook Watch.

- And the corollary seems to also be true with failed SVODs and streaming services — there’s no acquisition component, just a bunch of originals and licensed content to retain the audience that never came.

There are probably a bunch of examples that prove this thesis wrong, chief of which are Netflix and HBO. (But you could argue that they OVER spend on content, trying to force content into becoming an acquisition tool.)

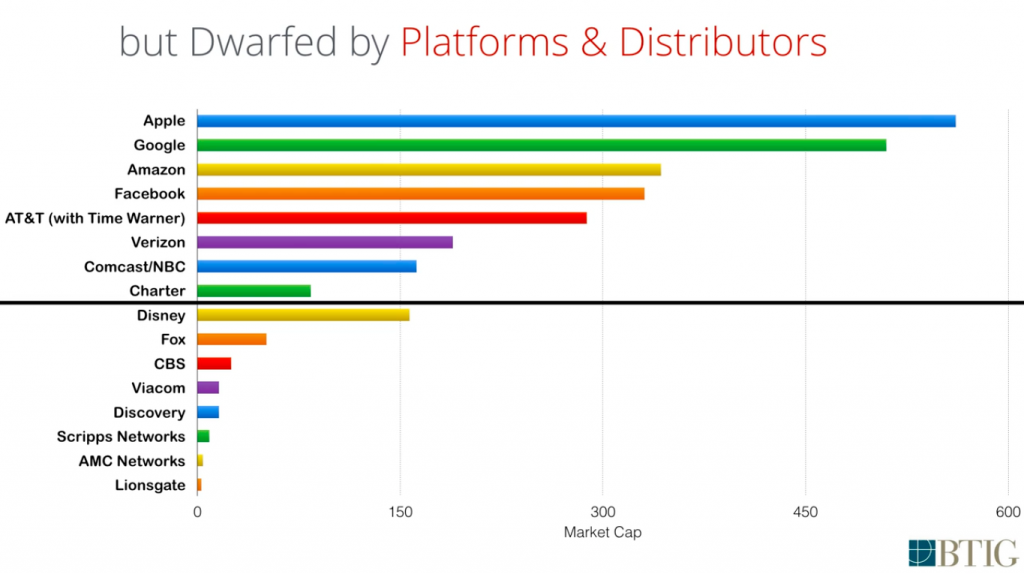

Even if it’s only a little true, it’s a helpful thought experiment: what if you had to launch a streaming service WITHOUT using content to acquire an audience? You’d have to offer real utility to your users — some other valuable product or service that would attract them to your subscription. Apple already has that part figured out: the phone, the ecosystem. And on the content side of your business, brands like Marvel, leagues like the NFL and celebrities like Oprah wouldn’t be as valuable because you already have a giant draw for new users. If your content is only playing the role of retention, it doesn’t need to hit an attention-grabbing must-see fever-pitch. It can be much less ambitious. You can spend way less than Netflix.