Netflix is killin it and I continue to be bullish on their future. There’s one corner of the business I’m afraid they’re being just a little too pensive about: mobile.

This year, they’ve launched some of their first short-form programming and some new native portrait features in their mobile apps. But I’m afraid this won’t stop other mobile competitors — Google and Facebook — from locking them out of this critical piece of the entertainment pie. Now is the time for them to begin spending in the mobile content space and here’s how they should begin.

Why mobile is critical to Netflix

Let’s start with why Netflix should care.

There’s an obvious massive market of short form video consumption, well-proven by YouTube and Facebook. 34% of global internet video traffic is shortform. So, when Netflix says they’re competing with all forms of entertainment, this seems like an obvious adjacent area to pick up some additional engagement — whereas interactive, live and sports are much more of a moonshot.

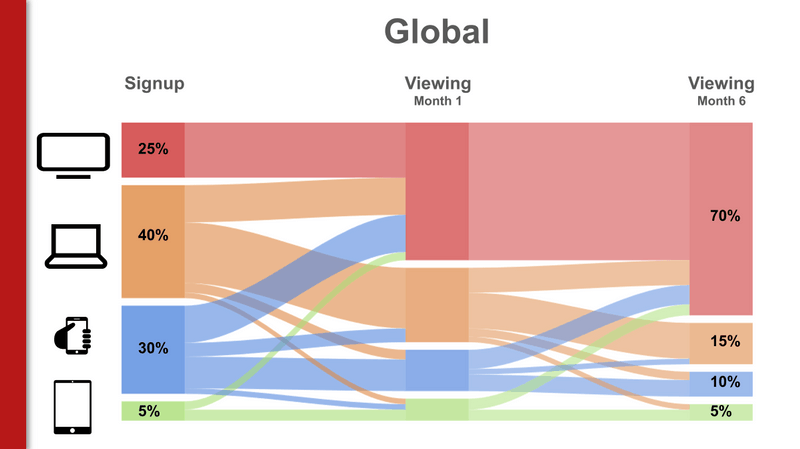

But I think all of that frames this as a business expansion opportunity when I actually think this is a threat to Netflix’s stranglehold on the streaming market. Have a look at this graph, which explains the userflow of new subscribers to the service.

When this slide first broke, a lot of emphasis was put on the fact that after 6 months, 70% of Netflix subscribers were watching on a big TV. What stands out to me is that 10% are STILL watching on a mobile phone. Just 1 month in, more than 15% are still struggling to watch long form TV shows and movies on a tiny mobile screen. And right from the getgo, a full THIRD of Netflix’s new users start on a mobile device.

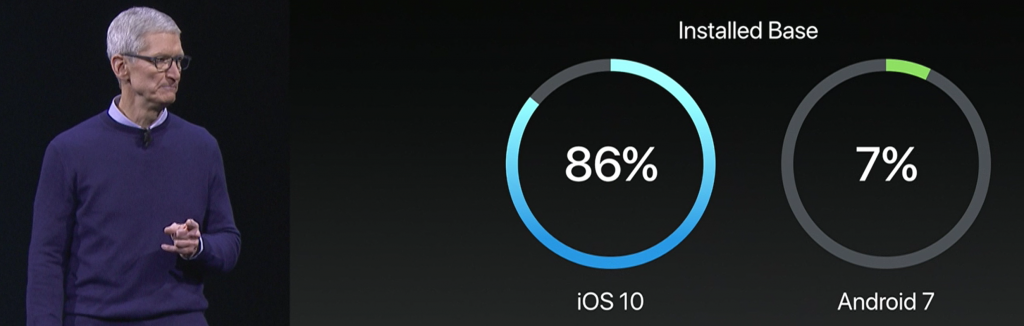

We are in a mobile world and who cares that people watch more content on their mobile phones — people TRANSACT more on their mobile phones. Enough people subscribe to Netflix straight through iOS that they’re trying to bypass Apple altogether — another sign of just how many folks sign up on mobile. Given that Netflix’s model is dependent on one giant transaction at the top of the funnel (their subscription), many more of their new customers are entering their ecosystem through mobile phones. And this user flows shows just how long it takes that mobile customer to begin finding big-screen-TV-type-value in their subscription. Were Netflix to actually provide valuable mobile content during that couple-month transition, they’d reduce churn among new users. (Still another strategy would be a freemium model of mobile-only content to lure users through the paywall when they realize the app’s value on another screen.)

What Netflix is already trying in mobile

Netflix is not completely blind to this. They’ve launched a few new short-form originals and mobile products this year. For those trying to reverse-engineer their mobile content strategy, here’s a recap of their short form content:

- The Comedy Lineup (15 minutes) – Mini stand-up comedy specials

- Explained (14-18 minutes) – Newsmagazine (Vox)

- Follow This (16-18 minutes) – Newsmagazine (Buzzfeed)

- Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee (12-25 minute) – Celebrity interviews with Jerry Seinfeld

- Marching Orders (12 minutes) – Docuseries

- Cooking on High (14 minutes) – Competition reality

In the scheme of Netflix’s $6 billion content spend, I’d call this an extremely modest beginning — it’s really just a test. It’s heavy on news and unscripted, there are no filmmakers, high-value talents or standout IPs. I estimate their 2018 spend on short form around $20MM at most. To make a meaningful move into mobile, they’ll need to spend 5-10x that.

How Netflix could form a mobile content strategy

It’s clear that Netflix needs to get into the mobile content game ASAP. But how? So many short form content platforms from go90 to Watchable have flamed out because of a lack of distribution.

Broadly, I’d approach this similarly to the rest of Netflix’s business:

- START FAST with a mountain of inexpensive mobile content that’s easy and fast to launch.

- PIVOT TO PREMIUM – Use the analytics gathered from starting fast to inform a mobile Originals strategy and finance exclusive new series.

Why this two-part strategy always works is the subject of a whole other blog post. But Netflix is in a unique position to build a war chest of start-fast mobile content at a low cost-per minute without sacrificing their premium values. Step one of fast/easy/quick mobile content — pretty obvious — is licensing. Now is a fantastic time to cheaply license premium mobile content. Every mobile content studio is clamoring to work with Netflix which earns them outrageous leverage. Plus, many of them were gifted back go90 or other mobile series that they have no place to distribute. The second source of start-fast content is probably less obvious: the content they already have. Netflix outright owns a lot of their shows and by getting creative, they’ll find a new life if they’re re-cut for a shorter runtime or carefully cropped for a vertical screen.

When audiences coalesce around their start-fast mobile content, they can decide where it makes sense to pivot to premium, maintain licenses or trim back.

In sum, I think mobile is a crucial growth area for Netflix and a place they have some natural competitive advantages. They could quickly turn a source of churn into a new source of revenue and expansion. I predict they’ll make some dedicated moves in this space but it’s going to take a larger commitment to realize the potential mobile content has in Netflix’s future.

Weighted way-too-heavily with tech platform executives, journalists and media moguls,

Weighted way-too-heavily with tech platform executives, journalists and media moguls,